Copyright is a fairly complicated area of the law that affects librarians in multiple ways. Whether helping an instructor with a course pack or trying to understand the licensing agreement on a piece of software or a Kindle, librarians need to understand at least the basics of copyright law. See the following video for an easy-to-follow overview of the subject (copyright basics at the CCC):

Copyright: What You Need to Know

Are you confused about Digital Rights Management? Do you wonder what DRM is all about? Take a look at this short (minute-and-a-half long), but informative video:

“Day by day and almost minute by minute the past was brought up to date. In this way every prediction made by the Party could be shown by documentary evidence to have been correct; nor was any item of news, or any expression of opinion, which conflicted with the needs of the moment, ever allowed to remain on record. All history was a (palimpsest), scaped clean and reinscribed exactly as often as was necessary.”

~ George Orwell, 1984, Book 1, Chapter 3 ~

Is digital publishing a good thing? A bad thing? A little of both?

Digital publishing allows information to be released quickly and disseminated widely. This can be both a blessing and a curse. Information that can be released quickly can also be deleted quickly. For instance, in July 2009, Amazon used a backdoor technology to delete purchased copies of George Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm from users’ devices. A Michigan teen sued the company after losing all of the notes that he had taken for his thesis. You can see more about this by visiting the following URL: http://www.foxbusiness.com/search-results/m/25662986/kindle-ate-my-homework.htm. With this level of control over content, what is to stop a company (or even a government for that matter) from simply deleting any material with which it disagrees? Some might argue that it would be impossible to make such information vanish on a medium as public and diffuse as the Web, but there is some evidence that it can happen. See the following article written by Newsweek reporter, Charla Nash: http://blog.newsweek.com/blogs/thehumancondition/archive/2009/11/13/charla-nash-on-oprah-what-happened-to-winfrey-s-chimp-lady-gaffe.aspx.

With digital publishing, information can also be hacked and distributed to unintended recipients. Take for example the announcement made yesterday that a secret manual produced by the Transportation Security Administration had been leaked on-line. This 93-page manual contained information regarding how often bags are checked for explosives, provided photographs of special identification cards, and showed examples of law enforcement and official credentials for federal air marshals, CIA officers, and members of Congress. See the following URL for more information: http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2009/12/08/eveningnews/main5942088.shtml. A key piece of national security data is now freely available on the Internet for any would-be terrorist or criminal to exploit. While it is true that print materials can also be copied and distributed to unwanted parties, doing so is considerably more difficult.

The Kindle is an electronic book reader that allows individuals to download digital content and to read it on the device. More specifically, the Kindle “is a portable electronic reading device that utilizes wireless connectivity to enable users to shop for, download, browse, and read books, newspapers, magazines, blogs, and other materials . . . .” (Amazon Kindle License Agreement, 2009, para. 1)

Since the Kindle first debuted in 2007 several libraries have decided to lend the device as a service to their patrons. For instance, the Sparta Public Library in New Jersey began lending Kindles in 2007, complete with content loaded onto the devices. (Oder, 2007, para. 1) Patrons were able to borrow a Kindle for one week at a time and to select one book apiece to upload from the Kindle shop. (Oder, 2007, para. 3) Many additional libraries throughout the country followed suit, including Brigham Young University in Utah, the Criss Library at the University of Nebraska-Omaha in Nebraska, the Howe Library in New Hampshire, and The Frank L. Weyenberg Public Library in Wisconsin. (Oder, June 2009, para. 1-2; Oder, April 2009, para. 4; Benson, 2009, para. 1)

While lending Kindles has proven to be a hit with library users, there remains some question as to whether doing so violates Amazon’s Terms of Use Agreement. Officially, Amazon has apparently indicated that lending a Kindle is a violation of the user agreement. (Oder, June 2009, para. 2) However, many libraries have been lending the devices for almost two years without adverse consequences. (Oder, June 2009, para. 2)

It appears that Amazon has been inconsistent in its stance on libraries lending the ebook reader. For instance, while the Howe Library has reported that it has contacted Amazon customer support and received verbal permission to loan the Kindle devices (Oder, April 2009, para. 1), Amazon spokesman Drew Herdener told a Library Journal staffer that Amazon policy prohibits “library lending, but ‘we don’t talk about our enforcement actions.’” (Oder, April 2009, para. 2)

In addition, while the Frank L. Weyenberg Public Library “has received written verification from Amazon” (Benson, 2009, para. 15) that they may circulate the Kindle, and Brigham Young University (BYU) has “received verbal permission from an Amazon rep.” (Oder, June 2009, para. 2) that it may do the same, BYU has suspended its Kindle lending program until it can get written confirmation that it is not doing anything illegal. (Oder, June 2009, para. 1)

In contrast, the librarians of the Criss Library at the University of Nebraska-Omaha (UNO) continue to lend Kindles to library patrons despite the legal uncertainty involved. (Oder, June 2009, para. 2) They do so under the belief that they are not violating the terms of use agreement. (Oder, June 2009, para. 3) Joyce Neujahr, director of patron services at UNO, explains their reasoning as follows: “We have purchased the content on the Kindle, and loan the Kindle just like we loan a hardcover, print book. The difference is where that purchased book resides. Whether it is on a shelf, or on a Kindle, we have still purchased the title.” (Oder, June 2009, para. 3) UNO law professors did not dissuade the library from lending the Kindles, as they “agreed that the terms of use seem to bar only profit-seeking efforts to distribute the digital content to a third party.” (Oder, June 2009, para. 4)

Legally, there seem to be two separate issues in play in this debate. First, is the issue of whether it is okay for libraries to lend the Kindle itself. Second, is the issue of whether it is okay for libraries to lend the digital content located on the Kindle device. To understand these issues it is first necessary to know a little bit about property law.

Property can be divided into two broad categories: real property (“realty”) and personal property (“personalty”). Real property is basically concerned with land and those things permanently attached to the land. (Black’s, p. 1234) Personal property (sometimes also called “chattel”), on the other hand, involves property that can be moved. (Black’s, p. 1233) Personal property can be further subdivided into two sub-categories: tangible personal property and intangible personal property. Tangible personal property is movable property that can be touched and felt. (Black’s, p. 1234) Examples of this type of property would be animals, furniture, clothing, jewelry, artwork, books, etc. Intangible personal property is moveable property that cannot be physically touched or felt (e.g., “property that lacks a physical existence”). (Black’s, p. 1233) Examples of this type of property would be money, stocks, bonds, copyrights, trademarks, and patents.

The law is clearly defined in regards to tangible personal property. A person who owns and has possession of a fax machine, for example, has the right to use, sell, lease, lend, and even destroy it. These rights derive from the legal concept of possession. “Possession is a property interest under which an individual is able to exercise power over something to the exclusion of all others. It is a basic property right that entitles the possessor to (1) the right to continue peaceful possession against everyone except someone having a superior right; (2) the right to recover a chattel that has been wrongfully taken; and (3) the right to recover damages against wrongdoers. Possession requires a degree of actual control over the object, coupled with the intent to possess and exclude others.” (Burke) Being that a Kindle is much like a fax machine, or a camcorder, or any other type of electronic gadget, there is no legal impediment to a library doing whatever it wants with the device once they have purchased it. Consequently, Amazon would most likely not have a valid cause of action against a library for loaning a Kindle with no digital content on it.

Unfortunately, the law is not quite as clear when it comes to the rights regarding intangible personal property. The digital content on a Kindle would constitute intangible personal property in that it is copyrighted material. While an exception to the copyright law known as “the first-sale doctrine” normally protects owners of physical books and CDs from claims of copyright infringement, the adoption of digital media and the implementation of digital rights management programs have made it more difficult to use this exception.

The first-sale doctrine is “the rule that a copyright owner, after conveying the title to a particular copy of the protected work, loses the exclusive right to sell that copy and therefore cannot interfere with later sales or distributions by the new owner.” (Black’s, p. 650) It is under the first-sale doctrine that owners of books, CDs, and DVDs are able to loan their copies of these materials to friends and family. While this is quite easy to do with a physical copy of a book, the matter becomes more complicated when the medium is digital in nature. As Francine Fialkoff notes in her editorial, To Kindle or Not: “libraries appear to be able to lend the device itself, but its content is locked up in its shrink-wrapped Terms of Service, which prohibits distribution to a third party. That means that whatever ebooks the library buys for it can’t be loaned. The Kindle is further limited by the proprietary nature of the software itself: ebooks purchased for a single Kindle can’t be transferred or shared, a deterrent for consumers as well.” (Fialkoff, para. 3)

While “most of us take for granted that books can be bought, sold, lent out and passed on . . . . according to Amazon, Kindle books are different. Customers never actually buy a digital copy. Instead they buy only a limited license to read that book in digital form. Amazon can revoke that license at any time and for any reason” under the Kindle Terms of Use. (Seringhaus, para. 5 & 7) The consequences of this became apparent in a somewhat dramatic fashion in July 2009 when “Amazon wirelessly reached into thousands of Kindle electronic reading devices and removed certain customers’ books.” (Seringhaus, para. 1) Ironically, the books that Amazon deleted were copies of George Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm. (Seringhaus, para. 1)

At this point in time, the legalities of lending Kindle devices containing licensed digital content are still unclear. Under the circumstances, libraries may want to take one of two approaches to solving this dilemma. For the more risk averse, it would make sense to contact Amazon to request written confirmation that it is permissible to lend the Kindles and the related ebooks. For those less worried about potential legal liability, it may make sense to take the “it is better to beg forgiveness than to ask permission” approach and to hope for the best. While the writer of this post is not advocating the latter approach, it is one possible way of addressing the Kindle lending issue. Ultimately, it behooves libraries to remember that Amazon has the power to simply delete content from library Kindles if it does not approve of libraries lending the devices.

REFERENCES

Amazon Kindle: License Agreement and Terms of Use (Last updated: February 9, 2009).

Retrieved from http://www.amazon.com/

Benson, D. (2009, March 21). Mequon library Kindles interest in digital device: Weyenberg is

the first in Wisconsin to loan out reading gadget. Milwaukee*Wisconsin Journal Sentinel.

Retrieved from http://www.jsonline.com/

Black’s Law Dictionary (7th ed. 1999).

Burke, B. (2003). Personal Property in a Nutshell, 3rd Ed. St. Paul: West.

Fialkoff, F. (2008, March 1). Editorial: To Kindle or Not. Library Journal. Retrieved from

http://www.libraryjournal.com/index.asp?layout=articlePrint&articleID=CA6533029

Oder, N. (2007, December 13). A New Jersey Library Starts Lending Kindles. Library Journal.

Retrieved from http://www.libraryjournal.com/

Oder, N. (2009, April 7). Mixed Answers to “Is It OK for a Library To Lend a Kindle?” Library

Journal. Retrieved from http://www.libraryjournal.com/

Oder, N. (2009, June 17). At BYU, Kindle Program on Hold, But University of Nebraska-

Omaha’s Program Going Strong. Library Journal. Retrieved from

http://www.libraryjournal.com/

Seringhaus, M. (2009, August 5). Kindle: How to Buy a Book but Not Own It – a Commentary

by Michael Seringhaus ’10. The Hartford Courant. Retrieved from

The End of Books?

Does the rise of digital content spell the end for physical books?

The following You Tube video asks an interesting question: In a world where everyone’s a publisher, where are the editors?

Can you see a problem with a world where there are no editors?

Can you see a potential problem with so much digital content being available for free?

Watch this two minute video and let us know what you think…

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JW8wa8rjsDM

There will be additional discussion on this topic in a follow-up blog post . . . .

“Libraries are reservoirs of strength, grace and wit, reminders of order, calm and continuity, lakes of mental energy, neither warm nor cold, light nor dark . . . . In any library in the world, I am at home, unselfconscious, still and absorbed.”

~ Germaine Greer ~

“What a place to be in is an old library! It seems as though all the souls of all the writers that have bequeathed their labours to these Bodleians were reposing here as in some dormitory, or middle state. I do not want to handle, to profane the leaves, their winding-sheets. I could as soon dislodge a shade. I seem to inhale learning, walking amid their foliage; and the odor of their old moth-scented coverings is fragrant as the first bloom of the sciential apples which grew amid the happy orchard.”

~ Charles Lamb ~

Physical libraries have been in existence for more than three thousand years. From the Library at Thebes in 1250 B.C. to the Library of Congress today, human beings have developed ways to store their information and have counted on librarians to preserve, protect, organize, and disseminate that information. In the quest to serve society’s information needs, librarians have utilized a vast array of processes and tools to do their jobs. These processes and tools have evolved and changed with the times. Some of the major advances in information science have included: the development of writing and paper, the invention of the printing press and books, the creation of library classification systems such as the Dewey Decimal System and the Library of Congress Classification System, the development of the card catalog, the implementation of electronic library cataloging systems like the MARC record, the adoption of personal computers, the availability of on-line searching, the addition of audiovisual materials to library collections, the adoption of the Internet, and heightened consumer demand for and use of technology. (Burke, 2009, p. 13-21)

However, libraries not only house technology – to a large extent, libraries are a form of technology. As author John J. Burke (2009) points out, “The library itself is a technology developed to handle information storage and retrieval” (p. 12). If libraries themselves are a type of technology, and technology is always evolving, then this begs the question: has the concept of the library shifted to a point where a physical library is no longer necessary? Have advances in computer and Internet technology converged to form a perfect storm of information storage and retrieval that will ultimately render physical libraries obsolete?

While some evidence exists that would seem to negate this conclusion, such as the fact that Ohio State University just spent three years and $109-million to renovate its 1913 library building (Carlson, 2009, para. 4), other evidence suggests that traditional book-based, physical libraries are in danger of becoming a thing of the past. For instance, in September of this year, The Boston Globe reported that a preparatory school in New England had become perhaps the first high school in the country to dispose of its book collection and replace it with computers, flat screen televisions, and digital devices. (Abel, 2009, para. 3)

In a news brief on the Cushing Academy website, the school says that it is: “. . . in the process of transforming [its] library into one that is virtually bookless by 2010.” (Cushing Academy, Newsbrief, 2009, para. 1) It further states that: “Space that previously housed bound books will become community-building areas where students and teachers are encouraged to interact, with a coffee shop, faculty lounge, shared teacher and students learning environments, and areas for study.” (Cushing Academy, Newsbrief, 2009, para. 3) The Globe noted that Cushing Academy will invest almost $500,000 to develop a “learning center,” complete with a $50,000 coffee shop and a $12,000 cappuccino machine in place of a reference desk. (Abel, 2009, para. 5) In lieu of the 20,000 books that the school once possessed, Cushing will offer eighteen electronic book readers and laptop-friendly study carrels instead. (Abel, 2009, para. 6)

In an on-line update from Cushing, Headmaster James Tracy stressed that the Academy’s goal in implementing this change is to provide greater accessibility to books, not less: “Our view of the matter is that we love books so much that we want our students to have dramatically increased access to millions of volumes rather than just 20,000. “ (Cushing Academy, Update, 2009, para. 4) As a rationale for the school’s decision to take the library digital, Tracy cited research undertaken by the school:

Our research found that, of a library of 20,000 printed books, only 48 were circulating at any given time, on average, and more than thirty of those were children’s books taken out by the families that live on campus. When we spoke with students, they told us that they were not using the books on-site for research, either. Teachers confirmed that students mostly cited on-line sources in their papers. We decided that we would provide students with much richer on-line database sources, including access to full-text, peer-reviewed journals, to teach them how to select out the most reliable content from all of the junk that they will encounter as students and professionals in the 21st century. The challenge today is how to teach students to cope with too much information, how to separate the wheat from the chaff. (Tracy, 2009, para. 7)

While whole-sale transformations from physical books to e-books is still rather rare, it is likely that more and more libraries will follow Cushing’s lead as technology continues to improve. This transition into the virtual realm may not herald the end of libraries as physical places, but it certainly portends a paradigm shift in the way that library spaces are designed and used.

Perhaps South Korea can provide us with a window on the future of library design. In May of this year, The National Digital Library (or dibrary) opened in Seoul with over 380,000 e-books and 116 million pieces of digital content. (Ji-sook, 2009, para. 1) Far from being a virtual library located solely in cyberspace, the new dibrary is an eight-story, 38,014 square-meter bricks-and-mortar building (Ji-sook, 2009, para. 1). Among the many innovations to be found at the library are: 626 desktop computers, notebook computers for rent from the main desk, flat-screen kiosks, video and audio recording studios for creating content, touch-screen satellite televisions, twenty-four computers programmed to operate in foreign languages (complete with matching alpha-numeric keyboards), and screen readers and other equipment to assist the visually impaired and those with physical disabilities. (Ji-sook, 2009, para. 3-8)

In describing the new library its director, Mo Chul-min, stated that “I can surely say our library will be the first and the largest ‘physical’ space to deal with online contents only.” (Ji-sook, 2009, para. 2) Although not without some potential difficulties, such as copyright issues revolving around the digitization of book content and market competition with e-book companies, the South Korean model of library design suggests a promising future for libraries as place. It should also be noted that The National Digital Library does not replace The National Library, which contains over seven million printed books, but rather serves to complement it. (Ji-sook, 2009, para. 10)

While physical libraries may survive in an altered form, if librarians want to remain relevant in this techno-savvy future they will need to embrace computer and Internet technology in a heretofore unprecedented manner. As the information that librarians have historically organized, catalogued, preserved, and disseminated in a print format continues to migrate to the digital realm, librarians will need to be comfortable with and adept at performing their functions in the virtual space. This will require librarians to understand at the very least the basics of how search engines operate, various computer applications function, and the capabilities of various electronic devices. As Michael Keller, the university librarian and director of academic information resources at Stanford University stated back in 2005, “The notion of a library as a physical collection has long ago been altered . . . . It’s now physical and virtual.” (Olsen, 2005, para. 3)

For centuries librarians have been charged with organizing and preserving ideas and information – whether those ideas were to be found on the clay tablets of Nineveh or on the papyrus scrolls of Alexandria or in the illuminated manuscripts of the Benedictine monks. In the end, libraries are more than physical repositories of information, and librarians are more than the professionals who manipulate physical objects in space. Perhaps Norman Cousins said it best when he stated that:

The library is not a shrine for the worship of books. It is not a temple where literary incense must be burned or where one’s devotion to the bound book is expressed in ritual. A library, to modify the famous metaphor of Socrates, should be the delivery room for the birth of ideas – a place where history comes to life.

With or without physical books, libraries and librarians will survive so long as there are ideas to be birthed and information to be organized and disseminated.

REFERENCES

Abel, D. (2009, September 4). Welcome to the library. Say goodbye to the books. Cushing Academy embraces a digital future. The Boston Globe. Retrieved from http://www.boston.com/

Burke, J. J. (2009). Neal-Schuman Library Technology Companion: A Basic Guide for Library Staff, 3rd ed. New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers, Inc.

Carlson, S. (2009, September 10). Ohio State U.’s Library Renovation is ‘Stupendous,’ Says a Leading Consultant. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/

Cushing Academy (2009, June 11). Newsbrief: Cushing’s e-Library. Retrieved from http://www.cushing.org/

Cushing Academy (2009, September 10). Library update from Headmaster Tracy. Retrieved from http://www.cushing.org/

Ji-sook, B. (2009, May 20). Library Going Digital. Korea Times. Retrieved from http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/

Olsen, S. (2005, August 3). The college library of tomorrow. CNET News. Retrieved from http://news.cnet.com/

Tracy, J. (2009, September 4). Re: Article in the Boston Globe about Cushing’s decision to take the library digital [On-line Live Chat Comment]. Retrieved from http://www.cushing.org/misc/library-live-chat.shtml

look @ this!

As if Text a Librarian wasn’t cool enough, look what’s coming next!!

Tweet a Librarian.

tweetalibrarian.com

Text a Librarian

I ♥ texting; Text a Librarian is a great new service that will appeal to fellow texters everywhere. People text twice as much as they talk, so this service really makes sense for libraries.

Curtis Marsh, director of the University of Kansas’s KU Info said, “We need to communicate with students the way they communicate with each other. It is about time we began offering our service through text messaging” (Library Journal, 2008, p. 22). This is a smart service for school libraries to offer to its patrons, as it probably appeals to students who text frequently. In turn, this makes the library appear hip and up to date, and could eliminate stereotypes of libraries being old dusty buildings with stuffy librarians.

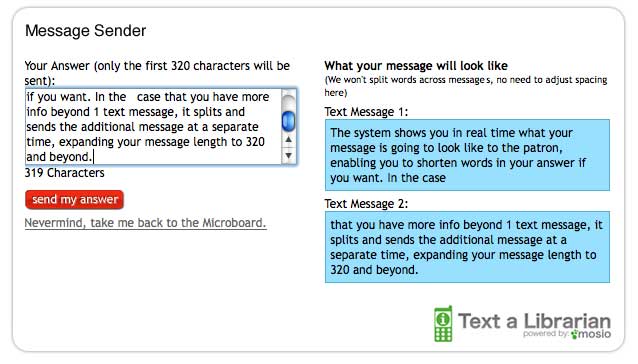

Some of you are probably wondering how this works, right? First, the library orders the Text a Librarian service (packages start at $99/month) and chooses a Microboard. A Microboard is the web-based area where the text questions pop up and answers are typed. Patrons can then text questions to your Microboard with their cell phones. Reference Librarians can then type the answer back to you, which you receive as a text message. omg way 2 cool :]

- Compose new SMS/Text Message to 66746

- Start your message with our keyword ASKTAL

i.e. asktal your message here - Send

You will receive an auto-response, one of the customizable features offered in the Text a Librarian service.

What are the advantages of using this service? http://www.textalibrarian.com shares some with us:

What are the advantages of using this service? http://www.textalibrarian.com shares some with us:

-

It is easy to implement, simple to use and IT-friendly.

-

Patron privacy is safe. Your data is secure.

-

Mosio’s Text a Librarian is not a hack.

-

Efficient for one librarian working alone or many working together.

-

Competitively-priced. Feature-rich. Always improving.

-

Run reports, gather stats and analyze usage.

-

We are technology compatible, perfect for Library 2.0.

Do you think academic AND public libraries should offer this service? Why or why not?

Do you see any disadvantages to a library purchasing this service?

Bibliography:

Text a Librarian from Mosio. (November 1 2008). Library Journal (1976). 133(18), 22.

Library technology skills survey

John J. Burke, author of Neal-Schuman Library Technology Companion: A Basic Guide for Library Staff, created a web survey in the fall of 2008 to determine how library staff members used technology on a day to day basis. 1,800 people responded from public, academic, school, and special libraries. This survey gives us a basic understanding of what types of technologies are used the most and which are used the least in libraries.

Technologies or technology skills used on a regular basis:

|

||||||||

| Technology or technology skill | Percentage of respondants | |||||||

|

97.9 |

||||||||

| Word processing |

96.2 |

|||||||

| Web searching |

94.1 |

|||||||

| Searching library databases |

92.7 |

|||||||

| Using an integrated library system |

86.3 |

|||||||

| Web navigation |

80.7 |

|||||||

| Teaching others to use technology |

79.1 |

|||||||

| Spreadsheets |

78.3 |

|||||||

| File management/operating system navigation skills |

62.3 |

|||||||

| Troubleshooting technology |

61.9 |

|||||||

| Presentation software |

60.1 |

|||||||

| Scanners and similar devices |

57.8 |

|||||||

| Database software |

54.1 |

|||||||

| Educational copyright knowledge |

47.6 |

|||||||

| Creating online instructional materials/products |

43 |

|||||||

| Making technology purchase decisions |

40.2 |

|||||||

| Installing software |

38.7 |

|||||||

| Web design |

36.7 |

|||||||

| Instant messaging |

32.6 |

|||||||

| Computer security knowledge |

28.4 |

|||||||

| Blogging |

28.2 |

|||||||

| Installing technology equipment |

24.9 |

|||||||

| Graphic design |

21.3 |

|||||||

| Assistive/adaptive technology |

18.1 |

|||||||

| Network management |

10.9 |

|||||||

| Other |

9.8 |

|||||||

| Computer programming |

8.5 |

|||||||

What technology do you use the most? What do you think is the most important and why?

Playaway

- Remember the days when cars didn’t have CD players in them? Listening to an audiobook on cassette was frustrating. The ability to push a fast forward button and skip from track to track was nonexistent. It took forever to find the chapter you were last listening to. You pressed fast forward and listened to it whir and hoped that you were a good guesser. You went too far ahead and then had to hit the rewind button. You had to go forward and backward until you found the right spot. God forbid the tape got stuck and all that brown stuff came out. What a mess.

- Then along came the audiobook on compact disc (CD). These were much better, but still had their issues. Longer books had ten or more CDs in one bulky box; the backs of the CDs were vulnerable and easily scratched, causing the CD to skip just when the book was really getting good. And as if concentrating on the road and the voice of the narrator was not multitasking enough, the CD came to an end, and you were left with anticipation as you struggled to drive, remove the current CD, and insert a new one.

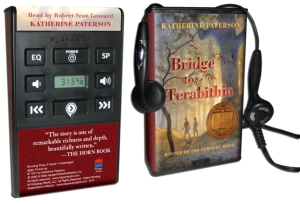

- The audiobook is a technology that has been evolving since the 1930s. The first audiobook was called a talking book, and it was used primarily by the blind. The audiobook on cassette became popular in the 1960s and the compact discs followed in the 1980s (Burke 2009). In 2005, a new audiobook technology emerged: the Playaway. A Playaway is a self-contained audiobook on an MP3 like player. It comes preloaded with an entire book and can store up to 80 hours of audio. It is smaller than a deck of cards and only weighs 2 ounces (Pope 2009). It comes with a lanyard (so you can wear it around your neck) but you can also plug it into your car if you have the right adapter. It has some really cool features that other formats of audiobooks do not. All of the command buttons are right there on the face of the unit: play, pause, stop, fast forward, and rewind. You can even speed up or slow down the voice of the reader, and when you turn it off it bookmarks where you left off!

- So, who uses Playaways anyways? They’re not just for the elderly or vision impaired. Playaway.com channels their audiobook to libraries and lending institutions; K-12 school libraries and classrooms; military troops, units, and base libraries; hospitals, senior living, and treatment centers. Basically, everyone can use a Playaway, which is what makes them so great. 50 year old Cindy loves listening to Dan Brown’s Davinci Code while she gardens, because it’s small enough to fit into her pocket. 16 year old Bryan listens to Walter Dean Myer’s Fallen Angels while he drives, as a nice escape from all the visual reading his high school teachers make him do for class. 9 year old Veronica listens to Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events in the car while her mom drives her to school. All it takes is 2 AAA batteries, some ear buds, a desire to read, and you’re ready to play away!

- Find out more about Playaways at http://www.playaway.com/

Bibliography:

Burke, J. (2009). Neal-Schuman library technology companion: A basic guide for library staff. New York: Neal-Schuman.

Pope, K., Peters, T., Bell, L., & Bastian, J. (2009, March). Find a Way to Offer Playaway: A New Kind of Audiobook. Searcher, 17(3), 50-51.